Family Planning and Access to Health Workers

This post was originally published on the IntraHealth International blog.

Amid the worldwide health worker shortage, some low-income countries are managing to show impressive levels of modern contraceptive use. How does access to skilled health workers affect family planning use, and what are some countries doing differently?

Fifty-seven countries have a critical shortage of health workers, and progress on the ground remains much slower than any of us would like to see—evidence from the Global Health Workforce Alliance suggests that only about half the national workforce plans are actually being implemented. Not one of these 57 health workforce “crisis” countries identified by the World Health Organization in 2006 has achieved the recommended minimum threshold of 2.3 doctors, nurses, and midwives per 1,000 people.

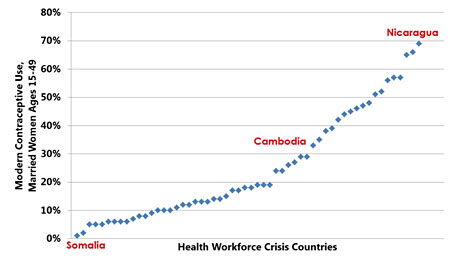

We might think it would follow that countries with a low density of doctors, nurses, and midwives relative to population would have similarly low levels of contraceptive prevalence. But this is not the case. In fact, there’s a huge spread among the health workforce crisis countries in terms of the contraceptive prevalence rate. Doctors, nurses, and midwives are only part of the story.

While all 57 crisis countries have critical shortages of health workers, some are achieving very different results in family planning. This heterogeneity seems to lie largely in how the countries are making use of paraprofessional health workers—those who are not trained at the same levels as doctors, nurses, and midwives. Community health workers, for example, play a vital role in many countries. Through the use of paraprofessionals, countries are handling their health workforce shortages differently, and getting different outcomes.

Increasing the density of doctors, nurses, and midwives has an impact on contraceptive use, according to data from the Health Workers Reach Index and the Population Reference Bureau, but if a country adds other types of health workers, the effect is dramatic. In Nicaragua, for example, 69% of married women ages 15-49 are using modern methods of contraception. Even in low-resource countries, we see that access to health workers improves family planning outcomes.

Sources: Save the Children UK, Health Workers Reach Index, 2011; Population Reference Bureau, World Population Data Sheet, 2011.

Women who aren’t using family planning have very little contact with health workers. A sample of a dozen health workforce crisis countries in Africa shows that the percentage of women not using family planning who have had contact with a provider never exceeds 20%, according to data from Demographic and Health Surveys 2006-2010. That means 80%-90% of women in these countries who aren’t using family planning have had no contact with a family planning provider. To be sure, some of these women may not be interested. But it’s likely that many of them have an unmet need for family planning and are not getting access to a provider.

At the International Conference on Family Planning in Dakar, I’ll be discussing this in more detail as part of a panel on addressing human resources for health barriers to achieving MDG 5b. What’s exciting to me is that significant progress in access to health workers is possible for almost every country. The choices made by national leaders will make the difference.

Related items:

Photo courtesy of IntraHealth International.