An academic culture of long working hours and the perception that faculty with family responsibilities are less committed affect decisions about promotions and tenure in both health professional education systems and other higher education institutions. A study of medical faculty with children in 24 US medical schools found that when compared with men, women had significantly fewer publications, self-reported slower career advancement, and lower career satisfaction (Reed and Buddeberg-Fischer 2001; similar findings in Reichenbach and Brown 2004). In 2009, half of the respondents of a University of California, Berkeley (US) faculty survey cited family/personal reasons as a very or somewhat important factor in accounting for slow or delayed career progression—second only to having a large service load (Stacy et al. 2011). Similarly, a study of academic faculty in the US and Australia found that higher proportions of female faculty in both countries did not request a reduced workload when they needed it for family reasons, because they believed it would negatively impact their careers and others’ perceptions of their seriousness as academics (Bardoel et al. 2011). Indeed, some Kenyan health professional education institutions may favor recruiting male faculty because they consider the possibility of female faculty taking maternity leave as disruptive (Newman et al. 2011). Especially for female faculty, occupational segregation can lead to inadequate representation in decision-making positions, limited career choices, delayed career advancement, and lower career satisfaction. However, faculty are generally motivated by opportunities for career development and leadership, as found in a study of faculty from seven nursing schools in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Bailey et al. 2012).

An academic culture of long working hours and the perception that faculty with family responsibilities are less committed affect decisions about promotions and tenure in both health professional education systems and other higher education institutions. A study of medical faculty with children in 24 US medical schools found that when compared with men, women had significantly fewer publications, self-reported slower career advancement, and lower career satisfaction (Reed and Buddeberg-Fischer 2001; similar findings in Reichenbach and Brown 2004). In 2009, half of the respondents of a University of California, Berkeley (US) faculty survey cited family/personal reasons as a very or somewhat important factor in accounting for slow or delayed career progression—second only to having a large service load (Stacy et al. 2011). Similarly, a study of academic faculty in the US and Australia found that higher proportions of female faculty in both countries did not request a reduced workload when they needed it for family reasons, because they believed it would negatively impact their careers and others’ perceptions of their seriousness as academics (Bardoel et al. 2011). Indeed, some Kenyan health professional education institutions may favor recruiting male faculty because they consider the possibility of female faculty taking maternity leave as disruptive (Newman et al. 2011). Especially for female faculty, occupational segregation can lead to inadequate representation in decision-making positions, limited career choices, delayed career advancement, and lower career satisfaction. However, faculty are generally motivated by opportunities for career development and leadership, as found in a study of faculty from seven nursing schools in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Bailey et al. 2012).

Sexual harassment

There is documentation of how resistance to unwanted sexual advances results in discriminatory promotion against female staff. In a study of Nigerian educational institutions, it was observed that efforts to enforce sexual harassment and equal opportunities tended to be bypassed by a strong “institutionalized masculine culture” that undermined women’s professional roles (Bakari and Leach 2007). Discriminatory promotion against female staff may be due to their resistance to sexual advances (Bakari and Leach 2007).

“A [university] staff member observed that if a woman refused to acquiesce to a man’s advances, he would make sure to campaign against her, for example, over a promotion.” —From a study of Nigerian universities (Bakari and Leach 2007)

Caregiver responsibilities discrimination

In competitive academic environments, gender stereotypes and discrimination against faculty with perceived caregiving responsibilities may persist, resulting in fewer “caregiver” faculty—most often female faculty— accessing career development opportunities and leadership roles. In competitive academic environments that require faculty to publish in order to be promoted or secure tenure, faculty with family responsibilities may face challenges to advance due to these rigid criteria. In the US, female medical faculty with children produced fewer publications (Reed and Buddeberg-Fischer 2001). Further, it has been documented that some employers at health professional institutions may view taking a reduced workload or time off for family responsibilities as a reflection of lower commitment to work, to the detriment of caregiving faculty seeking to advance their careers (US: Mason et al. 2005; Australia: Bardoel et al. 2011). Nearly two-thirds of female Australian university faculty agreed with the statement: “I came back to work sooner than I would have liked after having a new child because I wanted to be taken seriously as an academic”—significantly more than male faculty (Bardoel et al. 2011).

Women with family responsibilities may have particular difficulty meeting promotion requirements such as obtaining additional training that requires travel or seniority.

“By the time you come back [from childbirth or child-rearing], the men are long gone up the academic ladder.” —Ghanaian university faculty member (Adusah-Karikari 2008)

Suggested data analyses

Qualitative research, surveys, focus group discussions, or other special studies with health professional faculty can help you to understand the underlying factors and dynamics contributing to challenges in career advancement, and whether gender discrimination prevents male and/or female faculty from successfully progressing in their careers and assuming leadership positions.

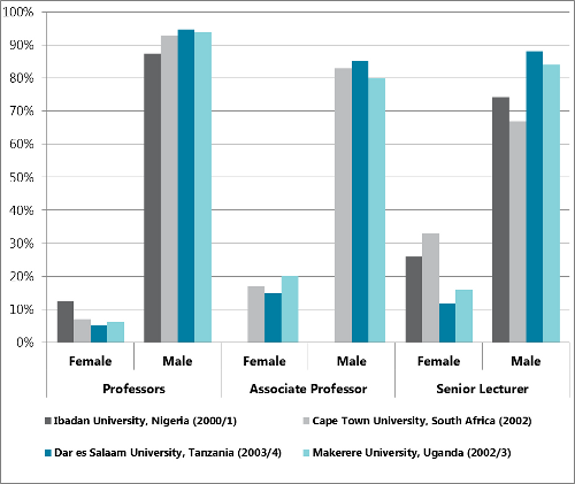

Sex-disaggregated analyses of faculty by position may reveal if gender discrimination affects your health professional education institution or system. In the charts below representing four African institutions, it can be observed that few women have academic appointments, with even fewer at higher-level positions.

Distribution of Academic Staff by Position and Sex, African Institutions

Source: Institute of Education, University of London, 2005.

Additional sex-disaggregated quantitative and qualitative criteria to assess faculty gender discrimination:

- Qualifications and age of academic staff

- Teaching load

- Publications per year

- Tenured vs. nontenured staff

- Average years to promotion

- Rate of accessing staff development opportunities or trainings

- Marital status, number of children

Ask Yourself:

|